Mary Caroline Stuart-Wortley on her Wedding day on 30th December 1880

Although needed at home to nurse her invalid father, Mary Stuart-Wortley wanted to be a professional artist. She even considered commercial work, notably designing greetings cards. Perhaps she hoped to supplement the family’s income. According to family tradition Mary yearned to be an artist from her youth: ‘She ardently wished to study painting, and she put all the force of an exceptionally strong will into becoming an artist. She decided to have training at the Slade School in Gower Street. Her parents always bent to her will and they agreed to this’ (Tweedsmuir 1952, p. 28). Unlike the Royal Academy Schools, the Slade, which opened in 1871, admitted both male and female students to the life classes.

Although Mary might have envied her brother Archie’s educational opportunities, he likewise enrolled at the Slade. Their attendance may have overlapped, as Mary was enrolled c.1872-73. She would have found herself in the company of Evelyn Pickering (1855-1919), who married William De Morgan in 1887 and Mary Fraser-Tytler (1849-1938), the second wife of the painter and sculptor George Frederick Watts.

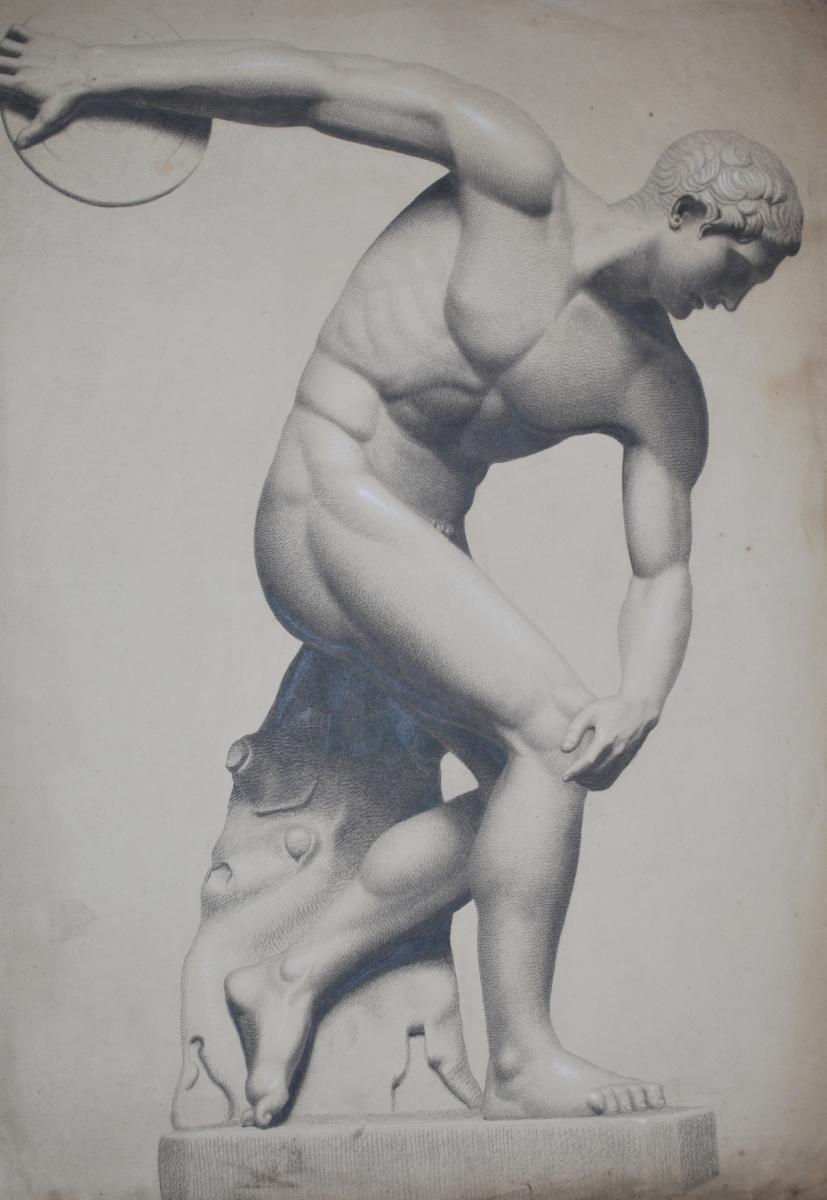

Drawings from cast and life undertaken by Evelyn De Morgan at the Slade School of Art, De Morgan Collection.

Apparently, Mary S-W hung her martial home Wentworth House with Evelyn’s paintings. Her family had little regard for them, although ‘they respected Evelyn de Morgan as a hard-working and dedicated artist’ (Tweedsmuir 1966, p. 23). I only painting I can securely document is The Sea Maidens (1886), as this was returned to Mrs Wilhelmina Stirling, Evelyn’s sister and biographer.

‘Aunt Mary had strong views about the necessity of helping artists of her date and age, and she inveighed against the many people who bought old masters or hung reproductions on their walls’. Mary preferred ‘the company of architects and craftsmen’ (Tweedsmuir 1966, p.23).

Susan Buchan, Lady Tweedsmuir claims that once married, her aunt had ‘to endure a quiet and ingrown existence’ (1966, p.22). Her ‘strange and lonely life caused her opinions to be frozen into the attitudes of her youth’. Mary, Lady Monkswell’s Diary, gives us a rather different picture of life at Wentworth House (Sat 16th March 1889; Collier 1944, p.148):

‘We dined with the Wentworths our neighbours & had the great, almost overwhelming honour of meeting the Grand Old Man (William Ewart Gladstone). I cannot say what I feel when I see him & consider his wonderful appearance his age (79), his past…I sat between an agreeable Mr Leveson Gower & Henry James, the American…Every word he says is worth taking down.’

Also present was Lady Compton, 5th Marchioness of Northampton (1860-1902) the Hon. Mary Florence Baring, daughter of the 2nd Baron Ashburton. Lady Monkswell noted ‘I should like to have her for a friend’. Apparently she was ‘the only child of an exigeante Mother & had to look after an exigeant husband & a very exigeant father-in-law’ (p.149). On the evening in question she was wearing black velvet with strings of diamonds & turquoises, ‘tall & pretty but extremely thin, which is not to be wondered at’.

Lady Monskwell observed: ‘Wentworth House was charming, full of old pictures, china and the central figure Lady Wentworth, with her fair hair, in white and diamonds’.

Lady Monkswell, nee Mary Josphine Hardcastle (1849-1930), married Hon. Robert Collier in 1873, becoming Lady Monkswell upon the death of her father-in-law Robert Collier, 1st Baron Monkswell (1817-1886).

Mary Hardcastle also enrolled at the Slade during its opening years, her attendance perhaps overlapping with her brother-in-law, the Hon. John (Jack) Collier (1850-1934), who took 1st prize for painting from life in 1874.

Mary Hardcastle, Lady Monkswell by the Hon. John Collier

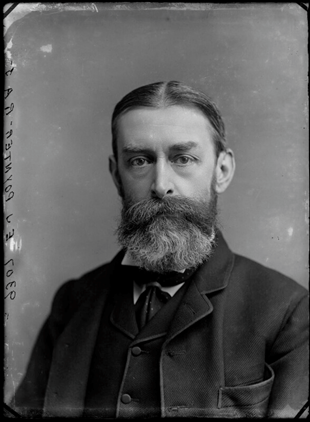

Portrait of the Hon. John Collier by his wife Marion Huxley (1859-87)

The Slade attracted serious female students from the middle and upper classes. Their aspirations were satirized by novelist Vernon Lee:

‘Young ladies, varying from sixteen to six-and-thirty, with hair cut like medieval pages, or tousled like moenads [sic], or tucked away under caps like 18th century housekeepers, habited in limp and stayless garments, picturesque and economical, with Japanese chintzes for brocade, and flannel instead of stamped velvet– most of which young ladies appeared at one period, past, present, or future, to own a connection with the Slade school, and all of whom, when not poets or painters themselves, were the belongings of some such’ (1884, p.309).

According to her niece, Mary S-W was the only girl in the family with no dress sense. Allegedly, she never wore corsets. Her family clearly regarded her as an ‘oddity’, referring to her paintings as ‘Mary’s Daubs’. Yet Mary was still anxious to safe-guard her social position as a respectable lady. Travelling from St. James’s Place to the Slade on Gower Street was a tricky task:

‘When she was young, no girl of quality could be seen alone in the street without scandal. She had to leave too early for the schoolroom party and their governess to be free to go with her. Her mother’s maid was busy with the much more congenial task of running up the seams of cheap stuff for ball dresses for the young ladies, and the daily ride in a four-wheeler (hansoms were barred as being too exposed to the public gaze) was much too expensive to be contemplated. However, by sheer force of character and insistence she managed to get an escort through the danger zone of Bond Street and Regent Street, where friends and acquaintances might be met. Then, alone, she embarked on a quick rush through the remaining streets till she reached the Slade, and she told me amusingly of her terror lest any friends, returning in a luggage-laden four-wheeler from King’s Cross or Euston, should catch a glimpse of her. After all these dangers were past, she stood at her easel all day, walked to within a shilling fare for a cab in the evening, and came home to amuse her invalid father’ (Tweedsmuir 1952, p.28).

Mary would have studied under Edward Poynter, Burne-Jones’s brother-in-law, who was appointed the first Slade Professor at University College in 1871.

Edward Poynter 1836-1919

Poynter forged a friendship with the Stuart-Wortley family through several different avenues. He was a close friend of Millais, who tutored Mary’s brother Archie. Through Millais, Poynter secured a prestigious commission from Edward Montagu-Stuart-Wortley-Mackenzie, Earl of Wharncliffe (1827-99), Mary’s cousin. Poynter was charged with decorating the billiard room of Wortley Hall, near Sheffield, in June 1871. Poynter’s pencil drawing of Margaret Stuart-Wortley, dated 1875, appears to have been a preliminary study for a portrait (Christie’s Victorian Paintings, 1995, Lot No.66, p.43).

It seems probable that Mary was introduced to Edward Burne-Jones by Poynter. Their relationship is dealt with in a further post.

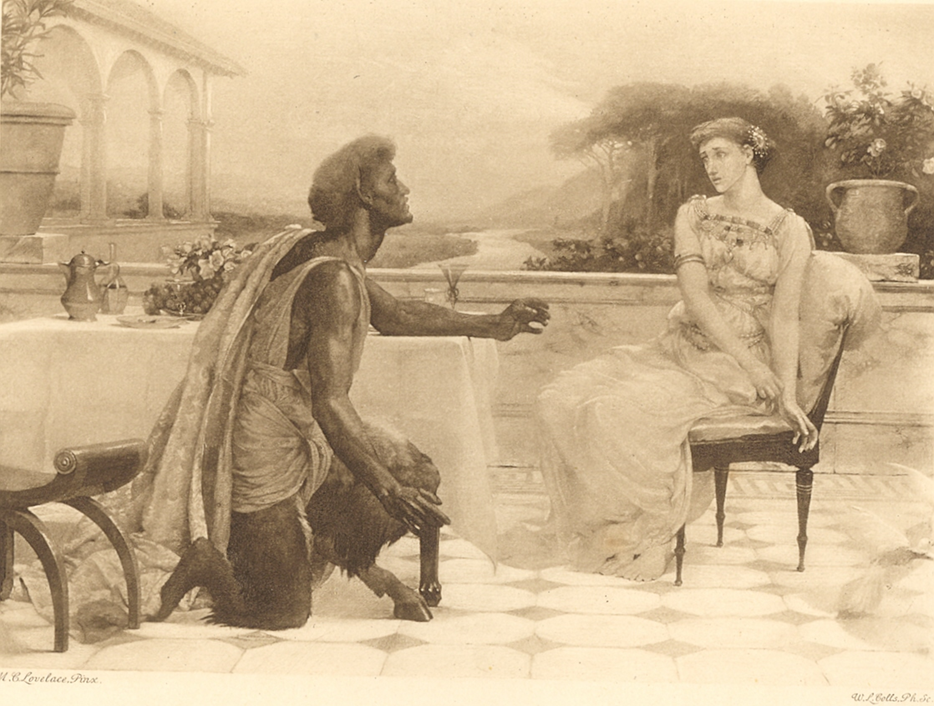

Although Mary allied herself to the avant-garde, preferring to show her paintings at the Grosvenor Gallery rather than the annual summer exhibition of the Royal Academy, her style was informed by Poynter’s academic standards. Her illustrations to The Story of Zelinda and the Monster or Beauty and the Beast, re-told after the old Italian version and done to pictures by Mary Stuart Wortley, Countess of Lovelace (London: Dent, 1895) would appear to place her amongst the so-called ‘Olympians’. The classical setting echoes paintings by Poynter and Lord Frederic Leighton.

There stood the Monster, and he came down to meet them.

“Zelinda, canst thou love me?”

Marriage did not deter Mary, Lady Wentworth from exhibiting. The following were shown at the Grosvenor Gallery, the titles giving us a good idea of the subject matter she was attracted too:

1879: Evening on the Cherwell

1882: Perdita

Here’s flowers for you; hot lavender, mints, savory, majoram.

The marigold that goes to bed wi‘ the Sun, And with him rises weeping.

1884: Bavarian Orchard

Marsh Marigolds

April Gardening

1885: In an upright country

Portrait of Five Sisters.

Of these works, only a photographic copy exists of Portrait of Five Sisters in the archives of the National Portrait Gallery. Mary based her self-portrait on an image by Frederick Hollyer (1837-1933), the famous photographer who reproduced many paintings by Burne-Jones. She sits with her face in profile, turned away from the viewer. Both the painting and the photograph depict a fashionably dressed lady, not the ‘oddity’ described by Susan Tweedsmuir.

References

Collier, Hon. E. C. F. 1944. A Victorian Diarist Extracts from the Journals of Mary, Lady Monkswell, 1873-1895, London: John Murray.

Lee, Vernon. 1884. Miss Brown A Novel. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons.

Tweedsmuir, Susan. 1952. The Lilac and the Rose, London: Duckworth.

Tweedsmuir, Susan. 1966. The Edwardian Lady. London: Duckworth.

Hello! What a nice surprise to see some information about the artist Mary Caroline Stuart Worley. My family owns the painting Perdita. Maybe you would like a photo. If so, I can be emailed at deborah-bailey@att.net

LikeLike

What a fascinating article. Many thanks. Archie her younger brother born in 1849 features in our book about the Hidden Artists of Barnsley https://barnsleyartonyourdoorstep.org.uk/book/9-Archibald-John-Stuart-Wortley.pdf

We are doing research currently into significant women in the lives of our artists and Lady Mary Lovelace will certainly be included in that work.

Hugh Polehampton, chair of Barnsley Art on Your Doorstep

LikeLike

Many thanks Hugh. My husband Scott features in your book as he researches W J Neatby!

LikeLike

Ah I hadn’t twigged to that! Of course. He gave an excellent talk during our exhibition too as well as writing the fine chapter about William Neatby. Give him our best wishes and thanks for replying to my comment. We are planning a talk about Barnsley’s past women artists and significant women in the lives of the others.

LikeLike